Economist and ecodharma activist Clair Brown calls on Buddhists to join the fight against climate change. What helps when the future looks bleak is the right kind of hope. Read more: https://www.lionsroar.com/right-hope/

Economist and ecodharma activist Clair Brown calls on Buddhists to join the fight against climate change. What helps when the future looks bleak is the right kind of hope. Read more: https://www.lionsroar.com/right-hope/

Economic inequality, with the rich showing off their wealth and superiority, is based on false beliefs about what makes us happy.

The Pandemic Gives Us Time to Ask What Makes Life Meaningful? in Psychology Today

Rich countries ship their own waste, especially plastic waste, out of sight while poorer countries who import shiploads of waste receive the brunt of the toxic effects.

Can we electrify our way out of climate change – or do the rich also need to consume less? in Developing Economics

People end up running after more income and competing incessantly with others, but without increasing their own well-being.

Make Black Friday meaningful: Give gifts that matter to people in the NY Daily News

In Big Tech and many other increasingly concentrated sectors, deregulation does not increase competition; on the contrary, it allows big companies to rig things in their favor.

What America Needs to Understand About Capitalism in Project Syndicate

The rich pollute the most and suffer the least from pollution.

Luxurious Lifestyles Are Hurting Us and the Earth in Psychology Today

BUDDHIST ECONOMICS: Living mindfully with love, compassion, and wisdom with Vajracaksu Dharmachari

Dr. Brown joined the City of Ten Thousand Buddhas’ Forum on Covid-19 to reflect on the Covid-19 pandemic. Exploring how during this pandemic, is it changing our way of thinking about life, and how to live a more meaningful life of awareness and compassion.

Watch the whole talk on YouTube here.

I grew up in Tampa, Florida. A lot of the people I know I’m pretty sure are Trump supporters, even relatives of mine. When we talk we talk about how’s your life going, what do you need in life? I probably harp too much on climate but I see it as an existential crisis that we have to take action on immediately. They often don’t know climate at all. What I’ve found out, especially for the Trump supporters, when I start talking about climate, they actually doo care. They do care about what the future will be like for their kids and grandkids. They’ve already suffered from extreme weather down in Florida and seen sea level rising. I’ve found if I can talk about things that are important to me and are important to them, we can agree on policies. A lot of the surveys from Pew or Data for Progress show that 70 to 80% of Americans agree on policies for stopping the climate crisis, for reducing inequality. So I don’t talk about Biden or Trump — what do we need in this country right now to improve people’s well-being? Because it’s amazing how we all actually do care about the same things, how to come together and care for each other and the planet. I find that’s really the only way to reach out and unite with other people.

University of Hong Kong: April 14, 2019

Watch here! (starts at 5:25 in)

“Economists sit around and fight about, are people altruistic or are they selfish? It really matters which kind of model you use. The free market model says they’re selfish and individualistic. The Buddhist Economics model says they’ve got to have some altruism and interdependence. Sociologists and neuroscientists confirm that people have altruism and self-regarding instincts — they do both. This isn’t a surprise, except to economists! Economists hate that answer, if they want to use the free market. People have unconditional caring about others without ulterior motive. Helping people and the environment makes you happy.”

Clair was featured in the Native Society:

Biggest Success?

A big accomplishment for me has been reaching out to and learning from people around the world, as we work together to stop selfish, materialistic forces from hurting people and the planet. Although we are in a dark period, many people are coming together to demand changes to heal the planet and care for people. I will continue to fight to keep the torch of meaningful, holistic economics alive and pushing forward.

Most Challenging Moment?

Being in a male-dominated field of economics is always a challenge. Female economists, from students to experienced faculty and practitioners, continue to face discrimination and sexist behavior. As women, we know to expect this, to fight against it, and to help each other. Although things are better today than forty years ago, we still have a long way to go to create a profession (and world) without race and gender bias.

Clair Brown, Professor of Economics, and Jun Pei Wong, economics major who is teaching a course on Ecological Economics, University of California, Berkeley.

This blog is based on a presentation made by Clair at Breakthrough Dialogue “Rising Tides” in Sausalito, CA: https://thebreakthrough.org/index.php/dialogue/breakth

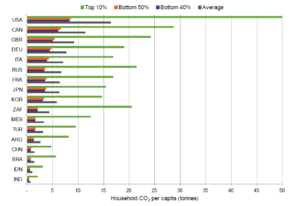

Our two biggest economic challenges—inequality and climate change—go hand in hand. Most of us know that poor countries and poor people in rich countries suffer the most from extreme weather, rising sea levels, and pollution. However you may not be aware that the carbon footprint of the rich is enormous as the rich live luxurious lifestyles with homes around the world, private jets, large yachts, exotic vacations, and closets full of things they don’t use. America’s 1 percenters emit fifteen times more greenhouse gas emissions per person than the average American and fifty times more than the average person worldwide (World Resources Institute). The rich pollute the most and suffer the least.

What do the rich achieve with their extravagant consumption? Not much from a social welfare or happiness viewpoint, as Buddhist economics explains. While a person shows off their self-importance, they are still wanting more because another rich person has an even longer yacht or bigger house. The valuation of consumption rests on comparing ourselves to one another. Thorstein Veblen, the 20thCentury economist who coined the terms “conspicuous consumption” and “invidious comparisons,” pointed out how individuals use luxury goods to show off their status. Veblen observed that people were living on treadmills of wealth accumulation, competing incessantly with others but rarely increasing their own well-being. This means that when inequality increases, we all feel less well-off even if our income has not gone down. When the rich get even richer and the rest of us don’t get more, our stagnant income and lifestyles seem diminished. Over the past four decades, economic growth has mostly gone to the top 5% of households, and this growth begets more inequality, without increasing social welfare as it exacerbates invidious comparisons. Yet inequality continues to increase in the US, with the top 1% grabbing 95% of income growth and the bottom 90% experiencing declining incomes even as the economy recovered (2009 to 2012) (Atkinson, Piketty, and Saez, JEL, 49 (1), 2011, 3-71).

Per capita emissions by income group for G20.

Source: Oxfam Report, Extreme Carbon Inequality, 2015. https://www.oxfam.org/sites/www.oxfam.org/files/file_attachments/mb-extreme-carbon-inequality-021215-en.pdf)

Feelings of social discontent and anxiety rise with growing inequality, and keep people fighting to maintain their social position even as those at the top aren’t feeling more satisfaction with their fancier lifestyles. With rising incomes comes frivolous spending, which itself drives ever more needless consumption, all so we can try to maintain our relative standing. This treadmill of wealth accumulation leads us to spend our incomes on status or luxury goods that tend to pollute the earth. Yet even though America’s top ten percenters emit six times the tCO2e of the bottom 50% of households (50 vs 8.5 tCO2e per person yearly; Oxfam), even the bottom 50% have an average carbon footprint that is four times the Paris Climate Accord goal of 2.1 tCO2e per person per year by 2050. The task to reduce CO2for the United States with 16.4 tCO2 is much greater than for the European Union with 6.7 tCO2. India and Indonesia will increase their carbon emissions as their living standards improve. Their people have very low emissions, below the 2.1 benchmark. (Girod, Env Research Letter, 2013.)Though there are improvements to be made across income groups and countries, the global rich need to lead the way in reducing their carbon footprint.

Rich countries are not the only ones vulnerable to this destructive story. The developing world faces enormous environmental degradation as the standard of living and the professional class imitates the lifestyle of the Western world based on subsidized fossil fuel energy. Countries such as China and India are already suffering the consequences of a burgeoning middle and upper class that consumes increasingly more. These populations are not only trying to keep up with the rich within their own countries but the global rich as well—this is evident where nearly all Chinese provinces and cities’ per capita carbon footprints increased from 2007 to 2010 (Shao et al. 2018). In India, poor urban slums (poorer areas) have lower carbon footprints than that of richer non-slum areas (Adnan et al. 2018).

The growing trend of inequality tells a stark story of economic growth without social welfare growth at the expense of a growing carbon footprint. If left unfettered, we can hardly progress in the right direction of reducing our carbon footprint. In order for the world to meet the Paris Climate Accord goal of 2.1 tCO2e, it should be clear that radical lifestyle shifts are critical. No longer would the rich consume mindlessly, and others caught up in the treadmill of wealth accumulation. Values such as those from Buddhist Economics should provide guidance. We derive happiness not from the pursuit of material goods or from “invidious comparisons,” but internally from each actor, rich or poor, to form an equitable and resilient economy and society. Only then will happiness decouple from our lifestyle emissions, and achieve the Paris Accord goals without sacrificing happiness and well-being.

“Thank you so much for your work to create an economy that works for all of us. And thank you for sharing your work with The MOON!” – Leslee Goodman, Pubisher & Editor, The Moon Magazine

Click Here: http://moonmagazine.org/creating-compassionate-economy-interview-clair-brown-2018-05-04/

On Saturday my family joined 60,000 people in Oakland, along with hundreds of thousands across the US, to protest Trumpism, which is harming people, killing the planet, and benefiting only the Rich.

We demand that Trump and his billionaire cronies stop harming immigrants, provide health care along with clean air and water to all Americans. Big Oil, Big Pharma, Big Military, and Big Bankers are in charge of our economy and government, and their greed and corruption are hurting us at home and harming people around the world.

Trump put the fossil fuel industry and investment bankers in charge of energy and the environment, and they are rolling back clean energy programs and pushing ahead with more drilling and pipelines for oil, goal, and natural gas on public lands and seas. The carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is rising rapidly and overheating the earth, but Big Oil puts profits before the health of people and the planet.

We must elect a new Congress in November! This was the main message of the Women’s March. We will continue working to defeat conservative Republicans in California and key spots across the country. We will stand up to Dark Money of the Koch Brothers and big companies, who think they can continue to buy Congress and Governors. We will raise money, and more importantly, we will VOTE!

Human nature includes both self-regarding (egocentric and taking care of oneself) and other-regarding (altruistic and taking care of others) impulses, and the well-being of humans and nature are intertwined. Even when economists believe that humans are not only selfish, opinions abound as to what degree human nature is egocentric and to what degree altruistic; and economists mostly ignore environmental problems.

Economists begin with the assumption that everyone is egotistical, and then they look to see if perhaps caring for others is possible. Economists have observed in lab games that most people have some altruistic feelings, defined as unconditional caring about others with no ulterior motive. Even in an experiment on what people expected from dictators, the subjects expected the dictators to be fair and not behave selfishly.[i] Generous behavior is not only observed in the lab, but also expected by subjects. These experiments have been important for economists to go beyond assuming that people are selfish and to incorporate other-regarding feelings into their models.[ii] Bowles and Gintis argue that humans developed cooperative instincts with moral sentiments over time to ensure group survival and growth. [iii] Now that the world is united by global warming, we have the opportunity to see how humans behave when existence is threatened in the short term, without time for evolution.

Buddhist economics complements the work of Bowles and Gintis. Yet rather than assuming basic human nature is selfish, and then asking what causes basically selfish people to become other-regarding, Buddhist economics sees human nature as altruistic, because people are interconnected with each other. Self-interest (ego) is developed as we grow up in a greedy materialistic world. We ask: “What creates materialistic self-interest (ego development), so people’s natural goodness becomes obscured by self-interest?” Certainly advertising creates endless desires; and inequality creates discontent as people compare themselves to the rich with their lavish lifestyles. Economic performance is measured by income growth, and society evaluates how well we are doing by how fast income is growing, while ignoring that the rich are getting most of the gain in income and our carbon emissions are overheating the planet and killing species.

Buddhist economics begins with the belief that our true nature is kind and altruistic, but then our ego obscures our true nature with delusions that lead to suffering from greed, hatred, and ignorance (the three mental poisons). The goal of life is to go beyond these delusions to be in touch with our Buddha nature, using contemplation and meditation along with our teachers and community of friends (sangha). Ignorance of our basic nature is the root cause of many of our personal, societal, and political problems, and failure to realize our own basic goodness or Buddha nature creates suffering.

We don’t have to agree to what extent humans act out of ego or altruism. What matters is that we agree that people have the desire, and responsibility, to take care of both themselves and others. Then the Buddhist economic system that redistributes income from the rich to the poor and caring about reducing suffering increases social welfare. We can make a living, even prosper, but not at the expense of others or the planet.

Audiences ask me about the violence and aggression promulgated by religions throughout history. Yet this observed violence and aggression is the result of confusion about who we are and how to attain eudaimonic happiness and relieve suffering. Violent behavior is never acceptable in Buddhist economics except to defend oneself and others in order to stop violence. Our mandate is to do no harm to sentient beings or to Mother Earth.

Without practicing Buddhism or any spiritual practice, one can adopt a pragmatic approach that accepts the interdependence among people and with nature, especially with global warming. In 1971, a founder of modern ecology, Barry Commoner, expressed this interdependence as one of the four laws of ecology: “Everything is connected to everything else. There is one ecosphere for all living organisms and what affects one, affects all.”[iv]

Then when nature is degraded, and when people are harmed, all life suffers.

As Thich Nhat Hanh writes, “Caring about the environment is not an obligation, but a matter of personal and collective happiness and survival. We will survive and thrive together with our Mother Earth, or we will not survive at all.”[v]

Image (under creative commons) from https://results.searchlock.com/search/?tbm=isch&q=buddha%20nature&slr=1&tsrc=a&sr=omniredir-ask&chnm=7bc02420-4653-4d94-b27a-19a3ca1f8d0c

[i] https://www.nature.com/articles/srep42446 (2017)

[ii] Andreoni et al, “Altruism in Experiments” Prepared for the New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, 2nd Edition, 2007

[iii] Samuel Bowles and Herbert Gintis, A Cooperative Species: Human Reciprocity and Its Evolution (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011).

[iv] Barry Commoner, The Closing Circle: Nature, Man, and Technology (New York: Random House, 1971).

[v] Thich Nhat Hanh, Love Letter to the Earth (Berkeley, CA: Parallax Press, 2013), p 82