Clair Brown, Professor of Economics, and Jun Pei Wong, economics major who is teaching a course on Ecological Economics, University of California, Berkeley.

This blog is based on a presentation made by Clair at Breakthrough Dialogue “Rising Tides” in Sausalito, CA: https://thebreakthrough.org/index.php/dialogue/breakth

Our two biggest economic challenges—inequality and climate change—go hand in hand. Most of us know that poor countries and poor people in rich countries suffer the most from extreme weather, rising sea levels, and pollution. However you may not be aware that the carbon footprint of the rich is enormous as the rich live luxurious lifestyles with homes around the world, private jets, large yachts, exotic vacations, and closets full of things they don’t use. America’s 1 percenters emit fifteen times more greenhouse gas emissions per person than the average American and fifty times more than the average person worldwide (World Resources Institute). The rich pollute the most and suffer the least.

What do the rich achieve with their extravagant consumption? Not much from a social welfare or happiness viewpoint, as Buddhist economics explains. While a person shows off their self-importance, they are still wanting more because another rich person has an even longer yacht or bigger house. The valuation of consumption rests on comparing ourselves to one another. Thorstein Veblen, the 20thCentury economist who coined the terms “conspicuous consumption” and “invidious comparisons,” pointed out how individuals use luxury goods to show off their status. Veblen observed that people were living on treadmills of wealth accumulation, competing incessantly with others but rarely increasing their own well-being. This means that when inequality increases, we all feel less well-off even if our income has not gone down. When the rich get even richer and the rest of us don’t get more, our stagnant income and lifestyles seem diminished. Over the past four decades, economic growth has mostly gone to the top 5% of households, and this growth begets more inequality, without increasing social welfare as it exacerbates invidious comparisons. Yet inequality continues to increase in the US, with the top 1% grabbing 95% of income growth and the bottom 90% experiencing declining incomes even as the economy recovered (2009 to 2012) (Atkinson, Piketty, and Saez, JEL, 49 (1), 2011, 3-71).

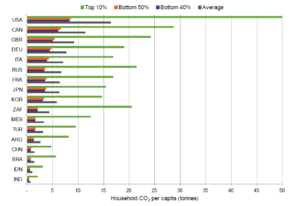

Per capita emissions by income group for G20.

Source: Oxfam Report, Extreme Carbon Inequality, 2015. https://www.oxfam.org/sites/www.oxfam.org/files/file_attachments/mb-extreme-carbon-inequality-021215-en.pdf)

Feelings of social discontent and anxiety rise with growing inequality, and keep people fighting to maintain their social position even as those at the top aren’t feeling more satisfaction with their fancier lifestyles. With rising incomes comes frivolous spending, which itself drives ever more needless consumption, all so we can try to maintain our relative standing. This treadmill of wealth accumulation leads us to spend our incomes on status or luxury goods that tend to pollute the earth. Yet even though America’s top ten percenters emit six times the tCO2e of the bottom 50% of households (50 vs 8.5 tCO2e per person yearly; Oxfam), even the bottom 50% have an average carbon footprint that is four times the Paris Climate Accord goal of 2.1 tCO2e per person per year by 2050. The task to reduce CO2for the United States with 16.4 tCO2 is much greater than for the European Union with 6.7 tCO2. India and Indonesia will increase their carbon emissions as their living standards improve. Their people have very low emissions, below the 2.1 benchmark. (Girod, Env Research Letter, 2013.)Though there are improvements to be made across income groups and countries, the global rich need to lead the way in reducing their carbon footprint.

Rich countries are not the only ones vulnerable to this destructive story. The developing world faces enormous environmental degradation as the standard of living and the professional class imitates the lifestyle of the Western world based on subsidized fossil fuel energy. Countries such as China and India are already suffering the consequences of a burgeoning middle and upper class that consumes increasingly more. These populations are not only trying to keep up with the rich within their own countries but the global rich as well—this is evident where nearly all Chinese provinces and cities’ per capita carbon footprints increased from 2007 to 2010 (Shao et al. 2018). In India, poor urban slums (poorer areas) have lower carbon footprints than that of richer non-slum areas (Adnan et al. 2018).

The growing trend of inequality tells a stark story of economic growth without social welfare growth at the expense of a growing carbon footprint. If left unfettered, we can hardly progress in the right direction of reducing our carbon footprint. In order for the world to meet the Paris Climate Accord goal of 2.1 tCO2e, it should be clear that radical lifestyle shifts are critical. No longer would the rich consume mindlessly, and others caught up in the treadmill of wealth accumulation. Values such as those from Buddhist Economics should provide guidance. We derive happiness not from the pursuit of material goods or from “invidious comparisons,” but internally from each actor, rich or poor, to form an equitable and resilient economy and society. Only then will happiness decouple from our lifestyle emissions, and achieve the Paris Accord goals without sacrificing happiness and well-being.